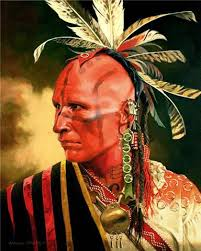

The Seneca were, and are, one of the Six Nations of the Iroquois, an Iroquoian-speaking people who originated in what is now New York, south of Lake Ontario. It's impossible to give more than a brief rundown of their history here, though we've already come across Seneca leaders such as Guyasuta, Red Jacket, Blacksnake, Cornplanter, Handsome Lake, and adopted Seneca such as Simon Girty and Mary Jemison. Their name, Seneca, in English comes from a corruption of the place-name of one of their villages, Osininka, which meant stone place in their language. Seneca oral tradition has them originating near Canandaigua Lake, at Bare Hill, where the remains of an ancient fort, said to have been inhabited by ancestors of the Seneca, once stood. The material of the fort was used in the early twentieth century as fill for a road, losing a valuable archaeological treasure.

The Seneca homeland was between the Genesee River and Canadaigua Lake. Along with the original Five Nations, the Seneca joined the Iroquois Confederacy in the 12th century. The Seneca extended their range to the Allegheny River after defeating the Wenro and Erie people during the Beaver Wars of the 17th century. Like the other Iroquois nations, the Seneca maintained farms and towns, but also hunted throughout their range, extended into the Ohio River Valley. The Seneca were rivals with other Iroquoian peoples such as the Huron and Susquehannock, and Algonquian speakers such as the Delaware and Shawnee. Seneca society was matrilineal, with children inheriting property and gaining status through their mother's tribe. During the Sullivan Expedition of 1779-80, American troops raided the Seneca heartland, taking note of the prosperous farms and towns.

Like the Mohawk, the Seneca emerged from the Beaver Wars as a formidable power to be reckoned with, having defeated other tribes and expanded their territory. They were allied with the British against the French, often facing French reprisals for their loyalty, particularly during the French and Indian/Seven Years War (1755-1763). However, during Pontiac's Rebellion (1764), some Seneca who had relocated to the Ohio Valley rebelled against British authority. At the beginning of the American Revolution (1775-1783), the Seneca had wanted to remain neutral. American raids on Seneca land forced them to choose sides with the British. This cost the Seneca most of their homeland in New York and thousands of Seneca relocated to Canada with the other Iroquois Nations. Leaders such as Red Jacket, Cornplanter and Blacksnake realized that making peace and coexisting with Americans would allow them to salvage some of their ancient homelands, although most of their land was eventually sold. Seneca living in Ohio were eventually forced to relocate to Oklahoma during Indian Removal in the 1830's. Today, there are three recognized Seneca tribes, Seneca Nation of New York, Tonawanda Band of Seneca Native Americans, and the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma.

Gayusuta and Washington

Tuesday, February 28, 2017

Monday, February 27, 2017

Settlers versus Natives: Kieft's War, 1643-45

The Dutch had an early presence in North America, in what is now New York and parts of Connecticut, but it wouldn't last beyond a few decades. This War is one of the reasons things went terribly wrong for the Dutch and it all stemmed from their misunderstanding of and high-handed treatment of the local Native tribes.

This war is sometimes capped the Wappinger War, but its more direct victims were the Lenape or Delaware. When the Dutch first arrived in North America, they had found the Delaware, Wappinger and the Pequot people to be ready allies, eager to trade beaver pelts for luxury items that became necessities in Native families. The Pequot War (1636-38) between Settlers what is now Massachusetts, eliminated the Pequot as a power in the region. English settlers allied with the Mohegan and Narragansett and began encroaching on Dutch territory in search of pelts and land. Meanwhile, maintaining and supplying the colony from home had become costly. The one thing they had going for them was the beaver trade, which was booming. Willem Kieft, appointed Director of New Netherland in 1638, had no prior experience heading a colony or dealing with Natives. His objective was to cut the costs of running the colony to maximize profit.

Among his first moves were to totally alienate his trading partners. He had a plan to make the colony pay for itself by demanding tribute from the Wappinger, Delaware and other tribes. This tribute was to take the form of food stuffs given to the colony from the Natives' own supplies. The Sachems of the tribes involved objected, pointing out that they needed this food to sustain their own families, too. A Settler, David de Vries, soon came to Kieft complaining that some pigs had been stolen from his farm. Kieft accused members of the Raritan, a tribe living on what is now Staten Island. He demanded that the Raritan produce the thieves for punishment. In fact, another Dutch settler had stolen the pigs and the Raritan were innocent. This alternative didn't occur to Kieft and he continued to threaten the Raritan, hoping to get results.

Then, in 1641, a Wappinger Native killed Claus Swits, an elderly Swiss colonist who ran a tavern in what is now Turtle Bay, Manhattan. There are various reports of the Native's motive, mostly having to do with vengeance for Swits or others having killed the man's relatives in an earlier ambush. Then, other Settlers became engaged in a brawl with Hackensack Natives over a lost or stolen coat and Kieft was fed up. He had his pretext for war on the surrounding tribes and he was quick to exploit it. In doing so, he was at odds with his own people. The Settlers of the colony realized that, surrounded as they were by so many Natives, with hostile English not far away, a war with the local tribes was the last thing they needed. Kieft created a Council of Twelve, whom he hoped would give him the mandate for war. They vetoed the idea instead. Kieft dissolved the Council and ordered an attack on villages of Wappinger and Tappan Natives in 1643.

In an incident known as the Pavonia Massacre, 120 Dutch Settlers killed over 120 Native men, women and children. The various tribes, all Algonquian-speaking, rallied in anger. A force of 1500 warriors invaded New Netherlands. One of their victims was Anne Hutchinson, who had fled Puritan Massachusetts and hoped to settle in peace with her family. As Kieft tried to rally Dutch settlers to fight the threat, many of them responded by fleeing the colony. Kieft hired English mercenary John Underhill, who killed over 500-700 Natives in the Pound Ridge Massacre. The Native tribes were ready to send in more warriors. Alarmed, the remaining Settlers in New Netherlands petitioned the Dutch West Indies Company and authorities in Holland to remove Willem Kieft.

While the Company and Dutch authorities back at home dithered in their response, the Settlers in New Netherland had a full-fledge Native revolt on their hands. Attacks followed each other back and forth. The English in Massachusetts and Connecticut saw a chance to exploit a weakness and began encroaching more on Dutch territory, often inciting the violence among rival tribes. Finally, in 1647, Dutch authorities recalled Willem Kieft, who died in a shipwreck on his way back to Holland to explain his conduct. Peter Stuyvesant was sent as Director to replace Kieft. He did manage to pacify the local tribes and put New Netherlands back in order, but the stage was set for further war. Ultimately, unable to bear the expense of supplying and defending their North American colonies, the Dutch would sell out to the English, but that's another post.

This war is sometimes capped the Wappinger War, but its more direct victims were the Lenape or Delaware. When the Dutch first arrived in North America, they had found the Delaware, Wappinger and the Pequot people to be ready allies, eager to trade beaver pelts for luxury items that became necessities in Native families. The Pequot War (1636-38) between Settlers what is now Massachusetts, eliminated the Pequot as a power in the region. English settlers allied with the Mohegan and Narragansett and began encroaching on Dutch territory in search of pelts and land. Meanwhile, maintaining and supplying the colony from home had become costly. The one thing they had going for them was the beaver trade, which was booming. Willem Kieft, appointed Director of New Netherland in 1638, had no prior experience heading a colony or dealing with Natives. His objective was to cut the costs of running the colony to maximize profit.

Among his first moves were to totally alienate his trading partners. He had a plan to make the colony pay for itself by demanding tribute from the Wappinger, Delaware and other tribes. This tribute was to take the form of food stuffs given to the colony from the Natives' own supplies. The Sachems of the tribes involved objected, pointing out that they needed this food to sustain their own families, too. A Settler, David de Vries, soon came to Kieft complaining that some pigs had been stolen from his farm. Kieft accused members of the Raritan, a tribe living on what is now Staten Island. He demanded that the Raritan produce the thieves for punishment. In fact, another Dutch settler had stolen the pigs and the Raritan were innocent. This alternative didn't occur to Kieft and he continued to threaten the Raritan, hoping to get results.

Then, in 1641, a Wappinger Native killed Claus Swits, an elderly Swiss colonist who ran a tavern in what is now Turtle Bay, Manhattan. There are various reports of the Native's motive, mostly having to do with vengeance for Swits or others having killed the man's relatives in an earlier ambush. Then, other Settlers became engaged in a brawl with Hackensack Natives over a lost or stolen coat and Kieft was fed up. He had his pretext for war on the surrounding tribes and he was quick to exploit it. In doing so, he was at odds with his own people. The Settlers of the colony realized that, surrounded as they were by so many Natives, with hostile English not far away, a war with the local tribes was the last thing they needed. Kieft created a Council of Twelve, whom he hoped would give him the mandate for war. They vetoed the idea instead. Kieft dissolved the Council and ordered an attack on villages of Wappinger and Tappan Natives in 1643.

In an incident known as the Pavonia Massacre, 120 Dutch Settlers killed over 120 Native men, women and children. The various tribes, all Algonquian-speaking, rallied in anger. A force of 1500 warriors invaded New Netherlands. One of their victims was Anne Hutchinson, who had fled Puritan Massachusetts and hoped to settle in peace with her family. As Kieft tried to rally Dutch settlers to fight the threat, many of them responded by fleeing the colony. Kieft hired English mercenary John Underhill, who killed over 500-700 Natives in the Pound Ridge Massacre. The Native tribes were ready to send in more warriors. Alarmed, the remaining Settlers in New Netherlands petitioned the Dutch West Indies Company and authorities in Holland to remove Willem Kieft.

While the Company and Dutch authorities back at home dithered in their response, the Settlers in New Netherland had a full-fledge Native revolt on their hands. Attacks followed each other back and forth. The English in Massachusetts and Connecticut saw a chance to exploit a weakness and began encroaching more on Dutch territory, often inciting the violence among rival tribes. Finally, in 1647, Dutch authorities recalled Willem Kieft, who died in a shipwreck on his way back to Holland to explain his conduct. Peter Stuyvesant was sent as Director to replace Kieft. He did manage to pacify the local tribes and put New Netherlands back in order, but the stage was set for further war. Ultimately, unable to bear the expense of supplying and defending their North American colonies, the Dutch would sell out to the English, but that's another post.

Sunday, February 26, 2017

Places: Mohawk Chapel, Brantford, Ontario

Beaver pelts weren't the only source of contention in North America. Both England and France felt they had a monopoly on the souls of the Native people in their respective territories. Catholic and Protestant missionaries operated among the tribes with equal zeal. Native leaders held their own views about which side was more beneficial to their people and weren't shy about asking rulers to intervene when necessary.

The three Mohawk Sachems who visited Queen Anne in 1710 included Teyoninhokarawan, who asked the Queen to send Anglican missionaries to the Mohawk. The Queen obliged, and also present the Mohawk with a silver communion service. Many Mohawk from New York became staunch Anglicans, foremost among them the Brant family. Joseph Brant and his sister Molly donated funds for a church to be built at Canajoharie, in New York, on land donated by Sir William Johnson. That church still stands. When the Mohawk were driven from their ancestral lands during the American Revolution, particularly the Sullivan Expedition of 1779-80, they sought refuge along the Grand River in Ontario.

The Mohawk Chapel was constructed in 1785. Originally, the entrance to the chapel faced east, to the river where a canoe landing area made for easy entrance. Leading people of the tribe including Joseph and John Brant and John Norton attended services here. Joseph Brant died in 1807 and was originally buried near his home in Burlington, Ontario. His remains were transferred to the chapel and buried in a tomb along with the remains of his son John, who died in 1832. Stained glass windows in the chapel commemorate episodes in Mohawk history, including Norton's translation of the Gospel of John. Queen Anne's silver communion service is kept at the chapel, which is one of two official Chapels Royal in Canada. The other, Christ Church Chapel Royal, near Deseronto, is also associated with the Mohawk people.

The three Mohawk Sachems who visited Queen Anne in 1710 included Teyoninhokarawan, who asked the Queen to send Anglican missionaries to the Mohawk. The Queen obliged, and also present the Mohawk with a silver communion service. Many Mohawk from New York became staunch Anglicans, foremost among them the Brant family. Joseph Brant and his sister Molly donated funds for a church to be built at Canajoharie, in New York, on land donated by Sir William Johnson. That church still stands. When the Mohawk were driven from their ancestral lands during the American Revolution, particularly the Sullivan Expedition of 1779-80, they sought refuge along the Grand River in Ontario.

The Mohawk Chapel was constructed in 1785. Originally, the entrance to the chapel faced east, to the river where a canoe landing area made for easy entrance. Leading people of the tribe including Joseph and John Brant and John Norton attended services here. Joseph Brant died in 1807 and was originally buried near his home in Burlington, Ontario. His remains were transferred to the chapel and buried in a tomb along with the remains of his son John, who died in 1832. Stained glass windows in the chapel commemorate episodes in Mohawk history, including Norton's translation of the Gospel of John. Queen Anne's silver communion service is kept at the chapel, which is one of two official Chapels Royal in Canada. The other, Christ Church Chapel Royal, near Deseronto, is also associated with the Mohawk people.

Saturday, February 25, 2017

The Treaty of Cusseta and the Creek War of 1836

The story of the removal of the Five Southeastern Tribes from their traditional homeland is one of broken promises, misunderstandings and outright betrayals. In the case of the remaining Upper Creek of Alabama, it was also a case of fake war.

The Muscogee/Creek people had once controlled vast acres of hunting rang in Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and northern Florida. By 1832, they were struggling to hold onto remaining lands in Alabama. Squatters continued to trespass on Native lands, even as land speculators had already claimed rights to it with state governments who were ready to see the Natives off to Indian Territory. Opothleyahola and other Creek leaders had achieved some partial damage control under the Treaty of Washington of 1826, but were still forced to give up all Creek land in Georgia. By 1832, authorities in Alabama were attempting to abolish tribal governance and extend state laws onto Creek territory.

The Muscogee/Creek people had once controlled vast acres of hunting rang in Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and northern Florida. By 1832, they were struggling to hold onto remaining lands in Alabama. Squatters continued to trespass on Native lands, even as land speculators had already claimed rights to it with state governments who were ready to see the Natives off to Indian Territory. Opothleyahola and other Creek leaders had achieved some partial damage control under the Treaty of Washington of 1826, but were still forced to give up all Creek land in Georgia. By 1832, authorities in Alabama were attempting to abolish tribal governance and extend state laws onto Creek territory.

In yet another attempt to salvage the situation, Creek leaders agreed to the Treaty of Cusseta of 1832, more cessions of Creek land in exchange for individual allotments of land for the remaining Upper Creek leaders and families remaining in Alabama. One leader, Ladiga, sold land forming present-day Jacksonville, Alabama for $2,000 at the time. The land speculators took advantage of Natives who did not understand American ideas of land ownership and induced them to sell their plots of land. Squatters simply moved in on other portions of land. Clashes broke out between squatters and Natives. Opothleyahola appealed to the Jackson Administration for help in preserving what little land his people had left. This was a last, desperate gasp, but one with some logic behind it. Although Jackson had signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Creek warriors had served with him in 1812, often fighting against their own people. They'd been promised annuities and land grants, which they never received. Perhaps the President would make good on his word.

No. The United States and Alabama authorities interpreted Creek attempts to dispossess squatters off their land as an act of war on the part of the Creek. Jackson ordered General Winfield Scott to send troops to forcibly remove the remaining Creek families off their land. Opothleyahola had no choice but to organize his people as best he could and lead them to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Opothleyahola would go on to honor and tragedy in Oklahoma, dying in 1863 after leading his people on the Trail of Blood and Ice trying to escape Confederate forces. Ladiga disappeared from history, commemorated today by a bike trail in Alabama that bears his name.

The Muscogee/Creek people had once controlled vast acres of hunting rang in Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and northern Florida. By 1832, they were struggling to hold onto remaining lands in Alabama. Squatters continued to trespass on Native lands, even as land speculators had already claimed rights to it with state governments who were ready to see the Natives off to Indian Territory. Opothleyahola and other Creek leaders had achieved some partial damage control under the Treaty of Washington of 1826, but were still forced to give up all Creek land in Georgia. By 1832, authorities in Alabama were attempting to abolish tribal governance and extend state laws onto Creek territory.

The Muscogee/Creek people had once controlled vast acres of hunting rang in Tennessee, Georgia, Alabama and northern Florida. By 1832, they were struggling to hold onto remaining lands in Alabama. Squatters continued to trespass on Native lands, even as land speculators had already claimed rights to it with state governments who were ready to see the Natives off to Indian Territory. Opothleyahola and other Creek leaders had achieved some partial damage control under the Treaty of Washington of 1826, but were still forced to give up all Creek land in Georgia. By 1832, authorities in Alabama were attempting to abolish tribal governance and extend state laws onto Creek territory.In yet another attempt to salvage the situation, Creek leaders agreed to the Treaty of Cusseta of 1832, more cessions of Creek land in exchange for individual allotments of land for the remaining Upper Creek leaders and families remaining in Alabama. One leader, Ladiga, sold land forming present-day Jacksonville, Alabama for $2,000 at the time. The land speculators took advantage of Natives who did not understand American ideas of land ownership and induced them to sell their plots of land. Squatters simply moved in on other portions of land. Clashes broke out between squatters and Natives. Opothleyahola appealed to the Jackson Administration for help in preserving what little land his people had left. This was a last, desperate gasp, but one with some logic behind it. Although Jackson had signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, Creek warriors had served with him in 1812, often fighting against their own people. They'd been promised annuities and land grants, which they never received. Perhaps the President would make good on his word.

No. The United States and Alabama authorities interpreted Creek attempts to dispossess squatters off their land as an act of war on the part of the Creek. Jackson ordered General Winfield Scott to send troops to forcibly remove the remaining Creek families off their land. Opothleyahola had no choice but to organize his people as best he could and lead them to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Opothleyahola would go on to honor and tragedy in Oklahoma, dying in 1863 after leading his people on the Trail of Blood and Ice trying to escape Confederate forces. Ladiga disappeared from history, commemorated today by a bike trail in Alabama that bears his name.

Friday, February 24, 2017

A Tale of Three Treaties

Treaties between colonial governments and Natives often led to more problems then they solved. There were several reasons for this, including the fact that these vast tracts of land were almost impossible to survey with precision, there was always self-dealing behind the scenes, and tribes with rights to specific hunting ranges were often overlooked. The Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued by George III's ministers in London with the intent to placate Native tribes after the Seven Years War (1755-1763), caused total chaos on the ground.

The Royal Proclamation forbade settlement beyond an imaginary line drawn along the Appalachian Mountain chain. The rule of thumb to differentiate open land from land off limits sounded simple enough. Settlement was permitted along those rivers which flowed into Atlantic. It was forbidden along Rivers which flowed into the Mississippi. This put the Ohio River Valley and Tennessee off limits to White settlement. The King's government reckoned without the rampant land speculation which took place during and after the war. Wealthy landowners such as Sir William Johnson and George Washington had already staked claims to lands in the Ohio Valley. Veterans of the War in most of the states had been promised land grants of seized French land as inducement to fight. The Royal Proclamation threw a sprig in all these schemes and something had to be done.

That something was the Treaty of Hard Labor signed between the Cherokee and John Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the British Indian Department in the South. Why this Treaty received its colorful name is not known today, except that it took all of Stuart's trust with the Cherokee and personal diplomacy to get it agreed to. The Cherokee agreed to give up claims to property west of the Allegheny Mountains and east of the Ohio River, namely all of present-day West Virginia. The line drawn ran from the junction of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers, to the headwaters of the Kanawha, then south to the boundary of Spanish Florida, well beyond the Proclamation line. Johnson signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in November, 1768 with the Iroquois, moving the Proclamation boundary west 300 miles.

There were immediate problems. For one, neither Stuart nor Johnson had reckoned with the Shawnee, Creek, or other Native tribes who also felt they had range rights in this land. Further, the boundary lines did not jive. Stuart called a parley with Cherokee leaders at Lochaber Plantation near Ninety-Six, South Carolina to redraw the lines again. The treaty line in the south was moved to six miles east of Long Island of the Holston River. The south fork of the Holston was agreed as the boundary. However, the generic designation of north or south of the Holston River caused immediate confusion as Settlers poured into the Holston, Nolichucky and Watauga River valleys of Tennessee, quickly lapping over into Cherokee territory. A survey confirmed that the boundaries lines of the Treaty of Lochaber were still not correct and settlers beyond the redrawn boundary were ordered to leave.

At this point, the Settlers decided to circumvent the crown, the Cherokee who were actually living on the contested ground, and land speculators in the east. They formed the Watauga Association and leased, later purchased the land from Cherokee leaders. In doing so, they reckoned without the Chickamauga Cherokee, who were not willing to cede any of their land. The Settlers also had another reason for grievance with the British crown, which refused to approve their purchase or defend them against Native attacks. On the frontier, the Revolution wasn't about taxation without representation. It was about land rights, pure and simple.

The Royal Proclamation forbade settlement beyond an imaginary line drawn along the Appalachian Mountain chain. The rule of thumb to differentiate open land from land off limits sounded simple enough. Settlement was permitted along those rivers which flowed into Atlantic. It was forbidden along Rivers which flowed into the Mississippi. This put the Ohio River Valley and Tennessee off limits to White settlement. The King's government reckoned without the rampant land speculation which took place during and after the war. Wealthy landowners such as Sir William Johnson and George Washington had already staked claims to lands in the Ohio Valley. Veterans of the War in most of the states had been promised land grants of seized French land as inducement to fight. The Royal Proclamation threw a sprig in all these schemes and something had to be done.

That something was the Treaty of Hard Labor signed between the Cherokee and John Stuart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the British Indian Department in the South. Why this Treaty received its colorful name is not known today, except that it took all of Stuart's trust with the Cherokee and personal diplomacy to get it agreed to. The Cherokee agreed to give up claims to property west of the Allegheny Mountains and east of the Ohio River, namely all of present-day West Virginia. The line drawn ran from the junction of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers, to the headwaters of the Kanawha, then south to the boundary of Spanish Florida, well beyond the Proclamation line. Johnson signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in November, 1768 with the Iroquois, moving the Proclamation boundary west 300 miles.

There were immediate problems. For one, neither Stuart nor Johnson had reckoned with the Shawnee, Creek, or other Native tribes who also felt they had range rights in this land. Further, the boundary lines did not jive. Stuart called a parley with Cherokee leaders at Lochaber Plantation near Ninety-Six, South Carolina to redraw the lines again. The treaty line in the south was moved to six miles east of Long Island of the Holston River. The south fork of the Holston was agreed as the boundary. However, the generic designation of north or south of the Holston River caused immediate confusion as Settlers poured into the Holston, Nolichucky and Watauga River valleys of Tennessee, quickly lapping over into Cherokee territory. A survey confirmed that the boundaries lines of the Treaty of Lochaber were still not correct and settlers beyond the redrawn boundary were ordered to leave.

At this point, the Settlers decided to circumvent the crown, the Cherokee who were actually living on the contested ground, and land speculators in the east. They formed the Watauga Association and leased, later purchased the land from Cherokee leaders. In doing so, they reckoned without the Chickamauga Cherokee, who were not willing to cede any of their land. The Settlers also had another reason for grievance with the British crown, which refused to approve their purchase or defend them against Native attacks. On the frontier, the Revolution wasn't about taxation without representation. It was about land rights, pure and simple.

Thursday, February 23, 2017

What Is It: A Matchcoat

Many portraits and sketches of woodlands people will show warriors and sometimes women with a blanket or large piece of cloth wrapped toga-style around the body. While today this is almost universally referred to as a blanket, it was known at the time as a matchcoat, after an English corruption of an Algonquian word for the garment.

In addition to breechcloths, leggings, tunics and other common pieces of Woodlands attire, Natives often used animal skins, sometimes with the fur side turned in during winter, as a combination blanket or cloak, particularly during winter months. Beginning in the 17th century, as trade between Natives and Europeans became common, woolen and other warm cloth became a trading staple, used for the same purpose. Wool is warm, even when it's soaking wet, and durable, standing up to repeated years of wash and wear, unlike animal skins. In addition to trade shirts or hunting shirts, Natives would wrap these large pieces of cloth around the body, sometimes securing them with a built or a sash, but never with pins or pieces of jewelry. In time, the simple lengths of cloth became more elaborate, with bands of colors died or woven into the fabric and arranged as part of the overall look. The matchcoat later became the blanket coat, a blanket folded or even sewn into a coat-like garment, called in French a capote, or the more well-known Trade or Point Blanket as sold by the Hudson's Bay Company, what many people commonly call an Indian Blanket.

In addition to breechcloths, leggings, tunics and other common pieces of Woodlands attire, Natives often used animal skins, sometimes with the fur side turned in during winter, as a combination blanket or cloak, particularly during winter months. Beginning in the 17th century, as trade between Natives and Europeans became common, woolen and other warm cloth became a trading staple, used for the same purpose. Wool is warm, even when it's soaking wet, and durable, standing up to repeated years of wash and wear, unlike animal skins. In addition to trade shirts or hunting shirts, Natives would wrap these large pieces of cloth around the body, sometimes securing them with a built or a sash, but never with pins or pieces of jewelry. In time, the simple lengths of cloth became more elaborate, with bands of colors died or woven into the fabric and arranged as part of the overall look. The matchcoat later became the blanket coat, a blanket folded or even sewn into a coat-like garment, called in French a capote, or the more well-known Trade or Point Blanket as sold by the Hudson's Bay Company, what many people commonly call an Indian Blanket.

Wednesday, February 22, 2017

The Place of the Whirlpool: the Wea

The Wea, or as they called themselves, the Waayaahtanwa, or people from the place of the whirlpool, were an Algonquian-speaking people closely linked to both the Miami and the Piankeshaw, whom we've covered in previous posts. They spoke a dialect of Miami shared in common with the Miami tribe. Origin stories for both the Piankeshaw and Wea also indicate a common origin. The main village of the Wea was Ouiatenon, in present-day Lafayette, Indiana. Concentrations of Wea were also present in Terre Haute, Indiana and Chicago, Illinois. The Wea were an important part of the Northwestern Confederacy of tribes opposing American incursion into the Ohio Territory. As such, they were present at several treaty parleys and signatories to treaties including the Treaty of Greenville (1795), the first Treaty of Fort Wayne (1803), the second Treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809, and Treaty of Fort Harrison, to name a few.

Though once a powerful tribe to be reckoned with, war, disease and displacement took their toll on the Wea. Most of the Wea went to Kansas in 1854 with the Kaskaskia, Peoria and Piankeshaw. They became the Confederated Peoria Tribe of Kansas and later the Peoria Tribe of Oklahoma after relocating there. Other Wea remained in Indiana, where they were known locally as Wabash Indians. Wea people survive today in Indiana, Oklahoma and elsewhere throughout the United States.

Though once a powerful tribe to be reckoned with, war, disease and displacement took their toll on the Wea. Most of the Wea went to Kansas in 1854 with the Kaskaskia, Peoria and Piankeshaw. They became the Confederated Peoria Tribe of Kansas and later the Peoria Tribe of Oklahoma after relocating there. Other Wea remained in Indiana, where they were known locally as Wabash Indians. Wea people survive today in Indiana, Oklahoma and elsewhere throughout the United States.

Tuesday, February 21, 2017

The Watauga Association

Life on the frontier was a system of improvisation. Far away from the usual sources of government such as legislatures and courts, citizens banded together and come up with their own forms of government. One of these, the Watauga Association, formed the nucleus of the modern state of Tennessee and was a source of constant conflict with the Chickamauga Cherokee and Settlers, and amongst the Cherokee themselves.

Beginning in the late 1760's and 1770's, Settlers mostly from Virginia began arriving in the Watauga, Nolichucky and Holston River Valleys in what is now northeastern Tennessee. They believed that these lands were part of a cession from the Cherokee to Virginia and that they had a right to settle there. However, a professional survey of the lands in question revealed that the land the Settlers were on was still part of the Cherokee domain and, more importantly, covered by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Dragging Canoe of the Chickamauga Cherokee didn't need a survey to tell him that Settlers were encroaching on his people's hunting range and he was determined to drive them away with a series of raids.

The Settlers in the three river valleys were ordered by royal officials to leave the area and took exception. Their leaders brokered a 10-year-lease with Cherokee and formed the Watauga Association, taking the name of one of the rivers. Subsequently, they purchased this land outright from the Cherokee. Both the lease and purchase were strictly illegal from the royal point of view. Further, Dragging Canoe, whose range was most affected, hadn't made any agreements with anyone and didn't believe himself bound to respect the settlements. Dragging Canoe allied with the British during the American Revolution, hoping they would enforce the Proclamation of 1763 and keep Settlers out of Chickamauga Territory. More settlers kept coming and, as the Revolutionary War loomed, they reformed their Watauga Association into the Washington District and petitioned Virginia to annex the area. Virginia refused and later North Carolina briefly annexed what would become present-day Washington and Carter counties in Tennessee.

Residence of the Wataugan lands were also known as the Overmountain men, rugged, tough farmers and settlers, of mostly Scottish, Irish or German extraction and allergic to rules or being told what to do. They formed their own ad hoc government, complete with courts and a militia, which they were ready to use. They were more than willing to defend their farms and settlements with their long rifles and were willing to take on Dragging Canoe. They formed the backbone of frontier militias commanded by men such as George Rogers Clark and John Sevier, and as such were constant enemies of Dragging Canoe and other Cherokee leaders trying to hold onto their land. Raids and reprisals went both ways between Settlers and Cherokee. Eventually, though, representatives of the Cherokee Nation ceded control of the Watauga, Nolichucky and Holston River valleys to White Settlement in 1777. The Chickamauga, though, weren't about to give up and continued the fight until the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794.

Beginning in the late 1760's and 1770's, Settlers mostly from Virginia began arriving in the Watauga, Nolichucky and Holston River Valleys in what is now northeastern Tennessee. They believed that these lands were part of a cession from the Cherokee to Virginia and that they had a right to settle there. However, a professional survey of the lands in question revealed that the land the Settlers were on was still part of the Cherokee domain and, more importantly, covered by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlement beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Dragging Canoe of the Chickamauga Cherokee didn't need a survey to tell him that Settlers were encroaching on his people's hunting range and he was determined to drive them away with a series of raids.

The Settlers in the three river valleys were ordered by royal officials to leave the area and took exception. Their leaders brokered a 10-year-lease with Cherokee and formed the Watauga Association, taking the name of one of the rivers. Subsequently, they purchased this land outright from the Cherokee. Both the lease and purchase were strictly illegal from the royal point of view. Further, Dragging Canoe, whose range was most affected, hadn't made any agreements with anyone and didn't believe himself bound to respect the settlements. Dragging Canoe allied with the British during the American Revolution, hoping they would enforce the Proclamation of 1763 and keep Settlers out of Chickamauga Territory. More settlers kept coming and, as the Revolutionary War loomed, they reformed their Watauga Association into the Washington District and petitioned Virginia to annex the area. Virginia refused and later North Carolina briefly annexed what would become present-day Washington and Carter counties in Tennessee.

Residence of the Wataugan lands were also known as the Overmountain men, rugged, tough farmers and settlers, of mostly Scottish, Irish or German extraction and allergic to rules or being told what to do. They formed their own ad hoc government, complete with courts and a militia, which they were ready to use. They were more than willing to defend their farms and settlements with their long rifles and were willing to take on Dragging Canoe. They formed the backbone of frontier militias commanded by men such as George Rogers Clark and John Sevier, and as such were constant enemies of Dragging Canoe and other Cherokee leaders trying to hold onto their land. Raids and reprisals went both ways between Settlers and Cherokee. Eventually, though, representatives of the Cherokee Nation ceded control of the Watauga, Nolichucky and Holston River valleys to White Settlement in 1777. The Chickamauga, though, weren't about to give up and continued the fight until the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794.

Monday, February 20, 2017

Places: Fort Moultrie and Osceola Gravesite

Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island in South Carolina wasn't on the frontier, but it did play a part during the American Revolution (1775-1783), the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) and the Civil War (1861-1865). Today it safeguards a tragic reminder of the Indian Removal of the 1830's, the grave of a man who had never wanted to leave his homeland in the first place and would've preferred to be buried anywhere else but there.

Fort Moultrie is one of several fortifications in Charleston Harbor, forming part of the coastal defense of the eastern United States. The first fort, built in 1776, was made of palmetto logs and named for Col. William Moultrie. More on him later, as he would also figure in the frontier wars with the Native Americans. The British bombarded the fort and fortunately enough for Moultrie and his men, the soft palmetto logs absorbed rather than broke under the cannon balls lobbed at them from British warships in the harbor. The British had to take the fort and the rest of Charleston by siege in 1780. They gave it up in the wake of Yorktown. The fort was strengthened in the years after the war, but destroyed in a hurricane in 1802. It would be rebuilt in the typical star-fort formation in 1808-09 and it was to this fort in December, 1836, that the Seminole leaders captured during the First Seminole War were brought.

By the time he arrived at Fort Moultrie, Osceola was a celebrity. His exploits had been the subject of newspaper articles. Painters flocked to paint his portrait even as it was obvious to those around him that the young war leader was dying of malaria complicated by quinsy. Perhaps realizing that his behavior would reflect on his people and how they were perceived and treated, Osceola mustered his strength and patience, arrayed himself in his finest regalia and sat for the portraits, developing a friendship of sorts with the post doctor, Frederick Weedon, and one of the portraitists, George Catlin. Contrary to popular myth, he was not kept in a dungeon, but in a room adjoining the fort's infirmary. He was allowed liberty of the walls during the day, meaning that he could walk around and wasn't shackled or mistreated. He was allowed to eat with the officers at their table and offered the same food, though Catlin noticed that Osceola refused liquor or wine as well as tobacco when offered to him.

Catlin left Sullivan's Island on January 26, 1830, and four days later, Osceola died. The body remained in the infirmary while preparations were made for a funeral. A grave was dug outside the gates of the fort and the body, minus its head, was carried there by soldiers and buried. A gun salute was fired over the grave. Osceola's family, colleagues and the garrison of the fort watched the proceedings from the battlements a few yards away. An admirer of Osceola's provided a headstone that included his name, dates and a simple epitaph "warrior and patriot". Within weeks, his family and the other Seminole leaders would be on their way to Oklahoma, officers and men would come and go, and in 1861, pro-Confederate forces took over Fort Moultrie, using its armament to batter Fort Sumter in the opening action of the Civil War.

Several ironclad battles took place in and around Charleston Harbor, which was heavily mined by the Confederates. The USS Patapsco struck a mine and blew up, killing all of her crew. Five bodies that washed ashore were given burial at Fort Moultrie, adjacent to Osceola's grave. A while obelisk marks the Patapsco monument. Brickwork and wrought-iron fencing surrounds both graves. Fort Moultrie was decommissioned in 1960 and turned over to the National Park Service. By that time, most of the internal buildings had been dismantled, including any sign of the infirmary room where Osceola would have spent his final days. Despite the fact that Osceola was buried without any regalia and thus nothing of value, rumors persisted of treasures buried with him and led to frequent attempts to vandalize the grave or claim that his bones had been located.

The grave was vandalized in 1967 and damaged in a rainstorm, forcing the Park Service to excavate the grave site. According to Patricia Wickman, Osceola biographer, the designated site with its brick overlay and wrought iron fence was just shy of the actual burial place, meaning that the grave robbers were unable to penetrate the coffin, which had been encased in cement and collapsed across the corpse over the years. The rumors that Osceola had been buried sans his head were proved true and a smaller coffin lay beside his, carrying the barely remaining bones of a tiny child. Whether it was his son or daughter who would've died at Fort Moultrie around the same time will never be known for sure. The grave was closed over and a replacement stone put over it. The original tombstone is in the visitor's center at the Fort.

Fort Moultrie is one of several fortifications in Charleston Harbor, forming part of the coastal defense of the eastern United States. The first fort, built in 1776, was made of palmetto logs and named for Col. William Moultrie. More on him later, as he would also figure in the frontier wars with the Native Americans. The British bombarded the fort and fortunately enough for Moultrie and his men, the soft palmetto logs absorbed rather than broke under the cannon balls lobbed at them from British warships in the harbor. The British had to take the fort and the rest of Charleston by siege in 1780. They gave it up in the wake of Yorktown. The fort was strengthened in the years after the war, but destroyed in a hurricane in 1802. It would be rebuilt in the typical star-fort formation in 1808-09 and it was to this fort in December, 1836, that the Seminole leaders captured during the First Seminole War were brought.

By the time he arrived at Fort Moultrie, Osceola was a celebrity. His exploits had been the subject of newspaper articles. Painters flocked to paint his portrait even as it was obvious to those around him that the young war leader was dying of malaria complicated by quinsy. Perhaps realizing that his behavior would reflect on his people and how they were perceived and treated, Osceola mustered his strength and patience, arrayed himself in his finest regalia and sat for the portraits, developing a friendship of sorts with the post doctor, Frederick Weedon, and one of the portraitists, George Catlin. Contrary to popular myth, he was not kept in a dungeon, but in a room adjoining the fort's infirmary. He was allowed liberty of the walls during the day, meaning that he could walk around and wasn't shackled or mistreated. He was allowed to eat with the officers at their table and offered the same food, though Catlin noticed that Osceola refused liquor or wine as well as tobacco when offered to him.

Catlin left Sullivan's Island on January 26, 1830, and four days later, Osceola died. The body remained in the infirmary while preparations were made for a funeral. A grave was dug outside the gates of the fort and the body, minus its head, was carried there by soldiers and buried. A gun salute was fired over the grave. Osceola's family, colleagues and the garrison of the fort watched the proceedings from the battlements a few yards away. An admirer of Osceola's provided a headstone that included his name, dates and a simple epitaph "warrior and patriot". Within weeks, his family and the other Seminole leaders would be on their way to Oklahoma, officers and men would come and go, and in 1861, pro-Confederate forces took over Fort Moultrie, using its armament to batter Fort Sumter in the opening action of the Civil War.

Several ironclad battles took place in and around Charleston Harbor, which was heavily mined by the Confederates. The USS Patapsco struck a mine and blew up, killing all of her crew. Five bodies that washed ashore were given burial at Fort Moultrie, adjacent to Osceola's grave. A while obelisk marks the Patapsco monument. Brickwork and wrought-iron fencing surrounds both graves. Fort Moultrie was decommissioned in 1960 and turned over to the National Park Service. By that time, most of the internal buildings had been dismantled, including any sign of the infirmary room where Osceola would have spent his final days. Despite the fact that Osceola was buried without any regalia and thus nothing of value, rumors persisted of treasures buried with him and led to frequent attempts to vandalize the grave or claim that his bones had been located.

The grave was vandalized in 1967 and damaged in a rainstorm, forcing the Park Service to excavate the grave site. According to Patricia Wickman, Osceola biographer, the designated site with its brick overlay and wrought iron fence was just shy of the actual burial place, meaning that the grave robbers were unable to penetrate the coffin, which had been encased in cement and collapsed across the corpse over the years. The rumors that Osceola had been buried sans his head were proved true and a smaller coffin lay beside his, carrying the barely remaining bones of a tiny child. Whether it was his son or daughter who would've died at Fort Moultrie around the same time will never be known for sure. The grave was closed over and a replacement stone put over it. The original tombstone is in the visitor's center at the Fort.

Sunday, February 19, 2017

Great Warrior: John Watts of the Chickamauga Cherokee

Dragging Canoe of the Chickamauga Cherokee was reckoned one of the best Native leaders and tacticians on the frontier. In an age of great military commanders in America and Europe, that Whites as well as Natives recognized his ability was an accolade. When he died in 1792, he would be a tough act to follow. But Dragging Canoe himself had already picked his successor, and it would be a good choice. John Watts.

John was the mixed-race son of a Scottish trader, also named John Watts, and a Cherokee woman. His mother was a sister of leaders and warriors such as Old Tassel, Doublehead, and Pumpkin Boy. One of her sisters may have been the mother of Sequoyah

. Watts would have received his warrior training from qualified men on his mother's side of the family, but he wouldn't come to Dragging Canoe's notice until later on. Watts was involved in raids against in combatting raids by American settlers into the Overhill Towns but it would be the murder of his uncle, Old Tassel in 1788 that would galvanize him to greater action. Watts would be a constant thorn in the side of John Sevier until the Chickamauga Cherokee signed the Treaty of Holston in 1791. Watts was one of the signatories. By this time, his qualities as a warrior and leader had Dragging Canoe's full attention.

When Dragging Canoe died in 1792, Watts was designated as his successor. In alliance with the Muscogee under Alexander McGillivray, he would continue the raids on Settlers pushing into the Overhill hunting range. In September, 1792, Watts planned his biggest engagement to date, a combined army of Creek and Cherokee, including a cavalry contingent. He divided up his forces into three groups to make a classic three-pronged assault that would've been devastating to the Settlers of Tennessee. Then, disaster struck. During a raid on Buchannan's Station, Watts and several other key Cherokee, Creek and Shawnee leaders were wounded or killed. The assault had to be postponed. Then, in 1793, a combined Cherokee and Creek peace delegation was ambushed and more leaders were killed. The perpetrators were rounded up, but acquitted in a kangaroo trial. Watts reassembled his army for a strike on Knoxville.

On their way there, the army diverted for a raid on Cavett's Station. Watts was one of those who opposed Doublehead's idea to kill all the Settlers. He, along with James Vann, was also angered by Doublehead's actions on this occasion. Doublehead and the Creeks parted company with Watts, Vann and the rest of the Cherokee contingent, again leaving Knoxville untouched for the time being. The Battle of Fallen Timbers and the collapse of the Native resistance in the Northwest Indian War convinced Watts that the Cherokee, too, must make peace. He was a signatory to the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794. He remained as Chief of the Chickamauga, but refused any offer of a seat on the National Council. In 1802, he died and was succeeded by Doublehead, which would only exacerbate the simmering feuds among the various Cherokee leaders.

John was the mixed-race son of a Scottish trader, also named John Watts, and a Cherokee woman. His mother was a sister of leaders and warriors such as Old Tassel, Doublehead, and Pumpkin Boy. One of her sisters may have been the mother of Sequoyah

. Watts would have received his warrior training from qualified men on his mother's side of the family, but he wouldn't come to Dragging Canoe's notice until later on. Watts was involved in raids against in combatting raids by American settlers into the Overhill Towns but it would be the murder of his uncle, Old Tassel in 1788 that would galvanize him to greater action. Watts would be a constant thorn in the side of John Sevier until the Chickamauga Cherokee signed the Treaty of Holston in 1791. Watts was one of the signatories. By this time, his qualities as a warrior and leader had Dragging Canoe's full attention.

When Dragging Canoe died in 1792, Watts was designated as his successor. In alliance with the Muscogee under Alexander McGillivray, he would continue the raids on Settlers pushing into the Overhill hunting range. In September, 1792, Watts planned his biggest engagement to date, a combined army of Creek and Cherokee, including a cavalry contingent. He divided up his forces into three groups to make a classic three-pronged assault that would've been devastating to the Settlers of Tennessee. Then, disaster struck. During a raid on Buchannan's Station, Watts and several other key Cherokee, Creek and Shawnee leaders were wounded or killed. The assault had to be postponed. Then, in 1793, a combined Cherokee and Creek peace delegation was ambushed and more leaders were killed. The perpetrators were rounded up, but acquitted in a kangaroo trial. Watts reassembled his army for a strike on Knoxville.

On their way there, the army diverted for a raid on Cavett's Station. Watts was one of those who opposed Doublehead's idea to kill all the Settlers. He, along with James Vann, was also angered by Doublehead's actions on this occasion. Doublehead and the Creeks parted company with Watts, Vann and the rest of the Cherokee contingent, again leaving Knoxville untouched for the time being. The Battle of Fallen Timbers and the collapse of the Native resistance in the Northwest Indian War convinced Watts that the Cherokee, too, must make peace. He was a signatory to the Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse in 1794. He remained as Chief of the Chickamauga, but refused any offer of a seat on the National Council. In 1802, he died and was succeeded by Doublehead, which would only exacerbate the simmering feuds among the various Cherokee leaders.

Saturday, February 18, 2017

Great Leader: Peter McQueen of the Creek

Behind every great man or iconic hero is, not only a great woman, but also a mentor and inspiration. The remarkable life story of Osceola began in the crucible of the Creek War (1813-1814) and he would've have plenty of powerful examples to draw on when his time came to take up his people's struggle. One was his own great-uncle, Red Stick leader Peter McQueen (1780-1820).

Peter was born in Tallassee, on the Tallapoosa River in Alabama, a town known for producing leaders among the Muscogee/Creek. His father, Alexander McQueen, was a Scots trader, and his mother was a Creek woman with status in her society that she could pass on to her children. Peter and his sister Ann were both leaders in their own right. It was Ann who whose daughter Polly was the mother of William (Billy) Powell, the boy who would become Osceola. In Creek society, the men of the mother's family provided the warrior training and mentored their nephews, sponsoring their introduction to men's society within the tribe. If Polly did not have brothers, the next logical one to provide such training and mentorship to young Billy would've been his great-uncle, who was both a war leader and a prophet/visionary.

Though the majority of Creeks, known as White Sticks, disregarded Tecumseh's pan-Indian movement, there were some among the Upper Creek towns who favored traditional ways and less coexistence with Whites. They were known as Red Sticks, for the ceremonial painting of their war clubs with red, the color for war. Peter McQueen, Josiah Francis, William Weatherford and Menawa were among a group of young war leaders who responded enthusiastically to Tecumseh's message and sought assistance from the Spanish and British to repulse American expansion on Creek land, and to oppose leaders such as William McIntosh who favored conciliation with the Americans.

After the ambush at the Battle of Burnt Corn in July, 1813, when Peter McQueen was leading a party of Creeks who'd obtained arms and ammunition from Spanish agents, war began in earnest between the two Creek factions. After the attack on Fort Mims in August, 1813, the United States became actively involved in putting down the Red Stick faction. McQueen was also part of the Native command team which faced Andrew Jackson at Horseshoe Bend in March, 1814. Following that battle, as McQueen and his warriors fled to fight another day, Ann, Polly and Billy fell into Jackson's hands as captives. Ann approached Jackson, offering to divulge her brother's whereabouts to obtain the freedom of the women and children. Likely, she had no idea where Peter and the others were and wouldn't have told Jackson accurately even if she did. Also likely, he wasn't fooled a bit, but needed a pretext to rid his camp of extra mouths to patrol and feed. If Jackson noticed a stripling 10-year-old who was no doubt learning how guile could help one survive, he gave no sign. Billy Powell would claim the attention of US authorities soon enough.

Ann and the others made good their escape and Peter led his people to join the Seminoles in Florida. There, while Francis went to England to press for aid from the British, McQueen masterminded the continued resistance to the Americans. He would lead Creek and Seminole war parties throughout the First Seminole War (1816-1818). His great-nephew would've been too young to be a warrior, but would've learned some lessons from the older man nonetheless. Josiah Francis was eventually hanged in 1816 and the revolt crushed. Peter, likely without his extended family, sought refuge on a remote island in Florida, some sources indicate one of the key islands, and died there in 1820. Fifteen years later, a man with McQueen lineage would rise to lead his people again.

Peter was born in Tallassee, on the Tallapoosa River in Alabama, a town known for producing leaders among the Muscogee/Creek. His father, Alexander McQueen, was a Scots trader, and his mother was a Creek woman with status in her society that she could pass on to her children. Peter and his sister Ann were both leaders in their own right. It was Ann who whose daughter Polly was the mother of William (Billy) Powell, the boy who would become Osceola. In Creek society, the men of the mother's family provided the warrior training and mentored their nephews, sponsoring their introduction to men's society within the tribe. If Polly did not have brothers, the next logical one to provide such training and mentorship to young Billy would've been his great-uncle, who was both a war leader and a prophet/visionary.

Though the majority of Creeks, known as White Sticks, disregarded Tecumseh's pan-Indian movement, there were some among the Upper Creek towns who favored traditional ways and less coexistence with Whites. They were known as Red Sticks, for the ceremonial painting of their war clubs with red, the color for war. Peter McQueen, Josiah Francis, William Weatherford and Menawa were among a group of young war leaders who responded enthusiastically to Tecumseh's message and sought assistance from the Spanish and British to repulse American expansion on Creek land, and to oppose leaders such as William McIntosh who favored conciliation with the Americans.

After the ambush at the Battle of Burnt Corn in July, 1813, when Peter McQueen was leading a party of Creeks who'd obtained arms and ammunition from Spanish agents, war began in earnest between the two Creek factions. After the attack on Fort Mims in August, 1813, the United States became actively involved in putting down the Red Stick faction. McQueen was also part of the Native command team which faced Andrew Jackson at Horseshoe Bend in March, 1814. Following that battle, as McQueen and his warriors fled to fight another day, Ann, Polly and Billy fell into Jackson's hands as captives. Ann approached Jackson, offering to divulge her brother's whereabouts to obtain the freedom of the women and children. Likely, she had no idea where Peter and the others were and wouldn't have told Jackson accurately even if she did. Also likely, he wasn't fooled a bit, but needed a pretext to rid his camp of extra mouths to patrol and feed. If Jackson noticed a stripling 10-year-old who was no doubt learning how guile could help one survive, he gave no sign. Billy Powell would claim the attention of US authorities soon enough.

Ann and the others made good their escape and Peter led his people to join the Seminoles in Florida. There, while Francis went to England to press for aid from the British, McQueen masterminded the continued resistance to the Americans. He would lead Creek and Seminole war parties throughout the First Seminole War (1816-1818). His great-nephew would've been too young to be a warrior, but would've learned some lessons from the older man nonetheless. Josiah Francis was eventually hanged in 1816 and the revolt crushed. Peter, likely without his extended family, sought refuge on a remote island in Florida, some sources indicate one of the key islands, and died there in 1820. Fifteen years later, a man with McQueen lineage would rise to lead his people again.

Friday, February 17, 2017

Did It Happen: Penn's Great Treaty of 1682

It's one of those enduring stories of Americana, much like Squanto and the Pilgrims or Pocahontas and John Smith. William Penn and Lenape/Delaware chief Tamarend (Tammany), meet under a giant elm tree in Shackamaxon, now within the city of Philadelphia, to agree a treaty of perpetual peace and unity with the language standard for every treaty, as long as the grass grows and river flows. The treaty was drawn up and signed by representatives of both sides and commemorated in wampum.

It's one of those enduring stories of Americana, much like Squanto and the Pilgrims or Pocahontas and John Smith. William Penn and Lenape/Delaware chief Tamarend (Tammany), meet under a giant elm tree in Shackamaxon, now within the city of Philadelphia, to agree a treaty of perpetual peace and unity with the language standard for every treaty, as long as the grass grows and river flows. The treaty was drawn up and signed by representatives of both sides and commemorated in wampum.So, did it happen? The answer, kind of

but not quite that way.

First, Shackamaxon, which some say translates from a Lenape word meaning "place of making chiefs" or maybe, "place of eels" was an important meeting place along the Delaware River. It was used by the Delaware as a meeting place for the selection and installation of headmen and sachems, and a summer rendezvous point for fishing. And, there was an elm tree there at one time. The key ingredient missing is a formal, written treaty. William Penn (1644-1718) was a devout Quaker. His faith forbade him to take a formal oath, but absolutely bound him to keep his word. By all accounts, he was respectful of the Natives and they were willing to assist with permission to settle on their land and not make war. Tamarend was a real person. However, there was no evidence that any written document was drawn up and signed. However, both sides acknowledged ever afterward that some type of agreement was reached at Shackamaxon. Delaware leaders referenced these treaty many times in subsequent meetings with Pennsylvania authorities. And, the Pennsylvania Historical Society has a wampum built which it believes was a memorial of treaty. But that still doesn't make up for the fact that there was never a signed writing.

First, Shackamaxon, which some say translates from a Lenape word meaning "place of making chiefs" or maybe, "place of eels" was an important meeting place along the Delaware River. It was used by the Delaware as a meeting place for the selection and installation of headmen and sachems, and a summer rendezvous point for fishing. And, there was an elm tree there at one time. The key ingredient missing is a formal, written treaty. William Penn (1644-1718) was a devout Quaker. His faith forbade him to take a formal oath, but absolutely bound him to keep his word. By all accounts, he was respectful of the Natives and they were willing to assist with permission to settle on their land and not make war. Tamarend was a real person. However, there was no evidence that any written document was drawn up and signed. However, both sides acknowledged ever afterward that some type of agreement was reached at Shackamaxon. Delaware leaders referenced these treaty many times in subsequent meetings with Pennsylvania authorities. And, the Pennsylvania Historical Society has a wampum built which it believes was a memorial of treaty. But that still doesn't make up for the fact that there was never a signed writing.The lack of written specificity would come back to haunt the Delaware years later, during the Walking Purchase of 1737, when Penn's two sons, Thomas and John, produced a document that they said was the treaty, along with a map specifying the treaty boundaries. According to these documents, the Delaware had ceded land as far as a person could walk in a day and a half. However, the rivers and landmarks specified in these documents were erroneous, and the appointed walkers turned the process into a footrace, cheating and outraging Delaware leaders. Most sources agree that while there may have been a spoken or gentleman's agreement between William Penn, Tamarend and other Delaware leaders, his sons had produced fraudulent documents and did their best to cheat the Delaware out of more land than the Natives contemplated by the Walking Purchase. Nevertheless, the Delaware made the best of a bad situation, moving further west and trying to coexist with the Settlers as best they could. And the treaty under the elm passed into legend, being celebrated by the French writer Voltaire, an early fan of the "noble savage" school of thought on Natives. The place where the elm and the treaty were thought to have occurred was made into a park in 1872.

Thursday, February 16, 2017

Creek Confederacy: the Koasati (Coushatta)

Just as the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples were composed of several different tribes, the Muscogee or Creek were not a single people, but rather many different tribes ranged throughout the Southeast. Throughout much of the frontier period, they were loosely grouped into an alliance called by Whites the Creek Confederacy, but each tribe was its own unit and decided for itself in matters of territory and how to deal with White encroachment on their lands.

The Koasati or Coushatta were one of the tribes encountered by Hernando de Soto in 1539-1543. Like other tribes in the area, they were grouped into towns and subsisted on hunting an agricultural diet of maize, beans and squash. The Spanish referred to them as Coste, and their neighbors included the Chiaha, Chiska, Yuchi, Tasquiqui and Tali. Due to pressure from White encroachment, they migrated to Alabama, where they established Nickajack Town, which we've already run across. They eventually migrated to the Tennessee/Alabama borderline. During the American Revolution and afterward they allied with other Creek tribes, tending to the Upper Creek or Red Stick view of keeping their own traditions as opposed to assimilating to European ways. They often allied with another Muscogean people, the Alabama, with whom their language was mutually intelligible.

Over time, some Coushatta chose to migrate to Lousiana and Texas to be free of White interference. Others remained in Alabama, where they experienced removal with the rest of the Creek people in 1830. Today, there are three federally-recognized tribes, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas and the Oklahoma-based Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town.

The Koasati or Coushatta were one of the tribes encountered by Hernando de Soto in 1539-1543. Like other tribes in the area, they were grouped into towns and subsisted on hunting an agricultural diet of maize, beans and squash. The Spanish referred to them as Coste, and their neighbors included the Chiaha, Chiska, Yuchi, Tasquiqui and Tali. Due to pressure from White encroachment, they migrated to Alabama, where they established Nickajack Town, which we've already run across. They eventually migrated to the Tennessee/Alabama borderline. During the American Revolution and afterward they allied with other Creek tribes, tending to the Upper Creek or Red Stick view of keeping their own traditions as opposed to assimilating to European ways. They often allied with another Muscogean people, the Alabama, with whom their language was mutually intelligible.

Over time, some Coushatta chose to migrate to Lousiana and Texas to be free of White interference. Others remained in Alabama, where they experienced removal with the rest of the Creek people in 1830. Today, there are three federally-recognized tribes, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas and the Oklahoma-based Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town.

Wednesday, February 15, 2017

Native Life: Hudson's Bay Point Blanket

Next to firearms and ammunition another coveted trade item was cloth or blankets, preferably woolen blankets that could stand up to any weather and be warm and durable even when wet. Beginning in the 17th century, French fur traders knew that the better the quality of woolen blankets offered, the better the beaver pelts in trade and vice versa. The Hudson's Bay Company, chartered in 1670, long offered generic woolen blankets as trade for beaver pelts. However, beginning in the 1780's, HBC came up with a more colorful and durable blanket to compete with whatever private or independent traders could offer.

It was called the point blanket. And, contrary to popular belief, the word point had nothing to do with the quality or quantity of pelts traded for each blanket, or the weight and grade of the woolen cloth. French woolen merchants had come up with a visual system for quickly and easily gauging the size of a blanket by a set of black threads woven into it. The number of these black lines, or points, denoted the overall size of the blanket. HBC point blankets were traditionally white, with dyed horizontal stripes woven into the cloth. The most favored colors for these stripes were yellow, green, blue and red. As with the points, the number and color of the stripes had nothing to do with the beaver pelts traded or quality of the cloth. These colors reflected the most cheaply available dyes at the time. These blankets were highly sought after for their durability and colorfast dyes. They could be made into blanket coats called capotes, a fashion adopted by both French-Canadian voyageurs and Natives alike.

HBC still manufactures the blankets today. While original blankets are prized collectors items, HBC point blankets in modern sizes are available in high end department stores such as Lord and Taylor.

It was called the point blanket. And, contrary to popular belief, the word point had nothing to do with the quality or quantity of pelts traded for each blanket, or the weight and grade of the woolen cloth. French woolen merchants had come up with a visual system for quickly and easily gauging the size of a blanket by a set of black threads woven into it. The number of these black lines, or points, denoted the overall size of the blanket. HBC point blankets were traditionally white, with dyed horizontal stripes woven into the cloth. The most favored colors for these stripes were yellow, green, blue and red. As with the points, the number and color of the stripes had nothing to do with the beaver pelts traded or quality of the cloth. These colors reflected the most cheaply available dyes at the time. These blankets were highly sought after for their durability and colorfast dyes. They could be made into blanket coats called capotes, a fashion adopted by both French-Canadian voyageurs and Natives alike.

HBC still manufactures the blankets today. While original blankets are prized collectors items, HBC point blankets in modern sizes are available in high end department stores such as Lord and Taylor.

Tuesday, February 14, 2017

Native Life: The Seven Cherokee Clans

The clan is an important concept in many tribal societies throughout the world. In many Native societies in North America, the clan was as important as a person's immediate family. Clan bloodlines, either matrilineal or patrilineal, depending on the tribe, held property and determined inheritance. They enforced laws against incest and adultery, as well as exacted vengeance for murder, thus exerting powerful social control. Often, membership in a clan determined who one could or could not marry. A man could not marry into his mother's, or sometimes his father's clan to prevent inbreeding and incest. Children were reckoned as belonging to their mother's clan and certain clans traditionally produced war or peace leaders or medicine men. Through the clan, women could exert as powerful an influence over family and tribal affairs as men.

Misunderstandings about how Native clans functioned produced the Indian Princess or specifically Cherokee Princess stereotype. Because women controlled land and land inheritance, and exerted wide authority in family and tribal matters, they were often assumed to be some kind of royalty. Most Native tribes in North America did not have a royal class, though elite status could pass down the generations. Thus, if an ancestor happened to marry a Cherokee woman who bestowed her status on her children and left them a claim to some property, later generations took to calling her a Princess and the rumors stuck.

According to the Cherokee Nation website, the seven Cherokee Clans, their subdivisions and traditional responsibilities are as follows:

LONG HAIR: subdivisions, Twister, Wind and Strangers. Peace chiefs would often come from this clan. Orphans, prisoners of war and adoptees from other tribes would be adopted into the subdivision of Strangers.

BLUE: subdivisions, Panther/Wildcat or Bear. They were responsible for making medicines specific to the protection of children.

WOLF: wolves are known to be fierce protectors. Thus, war chiefs would often come from the Wolf clan.

WILD POTATO: subdivision, Blind Savannah. These were the hunters and gatherers, known for their skill in finding the wild potatoes and other foodstuffs and conserving resources.

DEER: the people of this clan were also noted hunters and trackers. They were also used as scouts and messengers.

BIRD: subdivisions, Raven, Turtle, Dove and Eagle. These people were also scouts and messengers, not only between people and villages, but also between the spirit realm and humans. They collected the feathers used in ceremonies.

PAINT: these people were known as medicine men and women, harvesting and mixing medicines and officiating at ceremonies.

The clan system functioned until the Cherokee-American War (1775-1794), when migration and disruption broke up some aspects of Cherokee society. In the early part of the 19th century, some old customs were discontinued, such as blood vengeance and the allowance of patrilineal descent in certain circumstances.

Misunderstandings about how Native clans functioned produced the Indian Princess or specifically Cherokee Princess stereotype. Because women controlled land and land inheritance, and exerted wide authority in family and tribal matters, they were often assumed to be some kind of royalty. Most Native tribes in North America did not have a royal class, though elite status could pass down the generations. Thus, if an ancestor happened to marry a Cherokee woman who bestowed her status on her children and left them a claim to some property, later generations took to calling her a Princess and the rumors stuck.

According to the Cherokee Nation website, the seven Cherokee Clans, their subdivisions and traditional responsibilities are as follows:

LONG HAIR: subdivisions, Twister, Wind and Strangers. Peace chiefs would often come from this clan. Orphans, prisoners of war and adoptees from other tribes would be adopted into the subdivision of Strangers.

BLUE: subdivisions, Panther/Wildcat or Bear. They were responsible for making medicines specific to the protection of children.

WOLF: wolves are known to be fierce protectors. Thus, war chiefs would often come from the Wolf clan.

WILD POTATO: subdivision, Blind Savannah. These were the hunters and gatherers, known for their skill in finding the wild potatoes and other foodstuffs and conserving resources.

DEER: the people of this clan were also noted hunters and trackers. They were also used as scouts and messengers.

BIRD: subdivisions, Raven, Turtle, Dove and Eagle. These people were also scouts and messengers, not only between people and villages, but also between the spirit realm and humans. They collected the feathers used in ceremonies.

PAINT: these people were known as medicine men and women, harvesting and mixing medicines and officiating at ceremonies.

The clan system functioned until the Cherokee-American War (1775-1794), when migration and disruption broke up some aspects of Cherokee society. In the early part of the 19th century, some old customs were discontinued, such as blood vengeance and the allowance of patrilineal descent in certain circumstances.

Monday, February 13, 2017

Great Warrior: Bob Benge of the Chickamauga Cherokee

Time and again we've seen how mixed-race children of the frontier remained loyal to the Native side of their family. This feared Chickamauga warrior is another example. Bob Benge (C 1762-1794) was the son of a Cherokee woman and a Scots fur trader. He was tall, redhaired and his favorite weapon was an axe. As per custom with the Cherokee, he took his status from his mother's side of the family, where his great-uncles included Old Tassel and Doublehead, and his maternal uncle was John Watts, successor to Dragging Canoe. Any of these men were qualified to rear a young warrior on the right path and they did a good job. Captain Bench, or The Bench, as he was known to Whites, was a feared household name from Ohio to Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee.